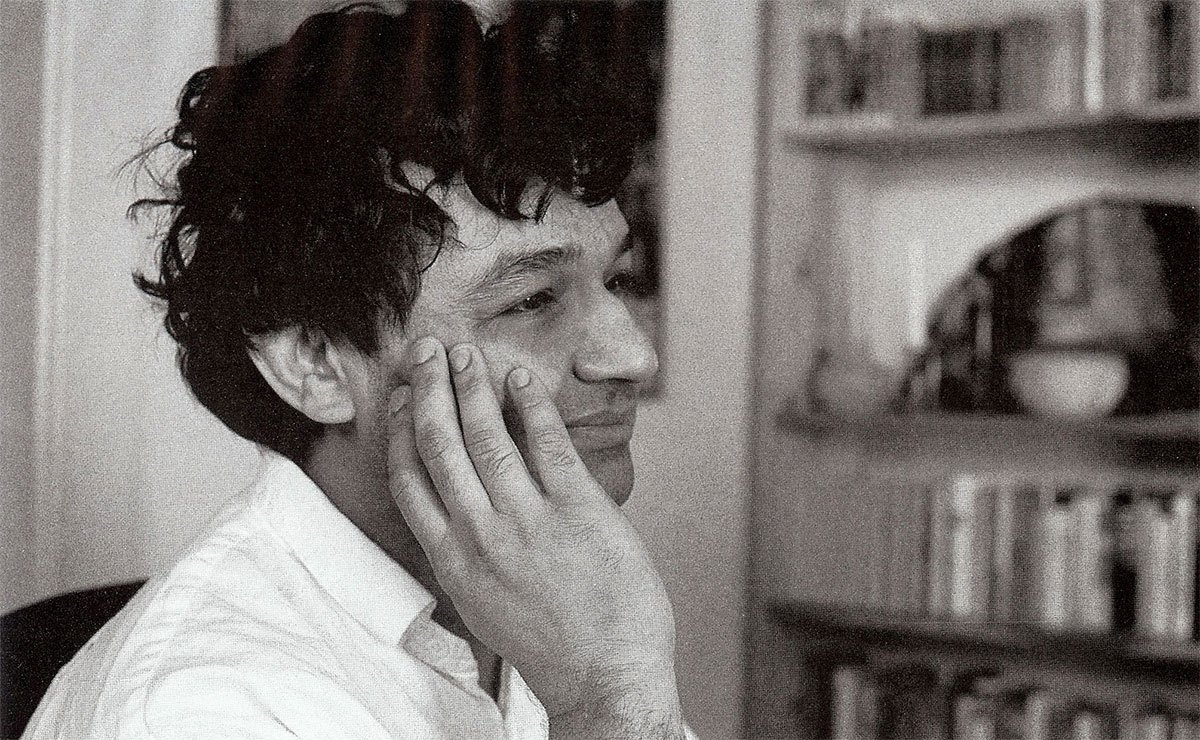

Agha Shahid Ali, as I understand it, better known in the U.S. (as an American poet) than he is in India or Pakistan. Though his writing is thickly influenced by the Persian-Urdu tradition (his style could be called ghazalesque), he wrote in English, not Urdu.

Shahid blended the rhythms and forms of the Indo-Islamic tradition with a distinctly American approach to storytelling. Most of his poems are not abstract considerations of love and longing, but rather concrete accounts of events of personal importance (and sometimes political importance). He was also intensely interested in geography, and often blended the landscapes of America (especially the southwest) with those of his native Kashmir.

The pleasure of reading Ali comes from the longer narrative poems. His short poem called “Memory” from Rooms Are Never Finished, shows Ali’s facility with lyricism in the English language — but which is clearly energized and imprinted by the Urdu tradition:

Memory

(from Faiz Ahmed Faiz)

Desolation’s desert. I’m here with shadows

of your voice, your lips as mirage, now trembling. Grass and dust of distance have let this desert bloom with your roses.

Near me breathes the air that’s your kiss. It smolders,

slowly-slowly, musk of itself. And farther,

drop by drop, beyond the horizon, shines the

dew of your lit face.

Memory’s placed its hand so on Time’s face, touched it

so caressingly that although it’s still our

parting’s morning, it’s as if night’s come, bringing

you to my bare arms.

Again, what I see in poems like this is not an attempt at ‘translating’ Urdu into English (this is in fact an adaptation of a Faiz poem). What Ali does is something much more subtle.

Ali’s poetry will be difficult for many readers unfamiliar with his references to the Indo-Islamic world, but also perhaps to the history of English and American poetry. Only a very small slice of readers will recognize Ali’s allusions to Merrill and Ghalib. It’s still worth the effort, and many of his poems do have footnotes explaining or translating key words or phrases.

One thing he will be known for beyond his poetry, I hope, is his book on Ghazals in English, Ravishing Disunities: Real Ghazals in English. His introduction is one of the small masterpieces in postcolonial literary criticism, helpful for its straightforward explanation of the historical context of the ghazal, for its concise technical definition, as well for its exploration of the adaptability of the Ghazal to the English language. Here is a bit from Ali’s account of the emergence of the Ghazal form:

[T]he ghazal goes back to seventh-century Arabia, perhaps even earlier, and its descendents are found not only in Arabic but in–the following come spontaneously to mind: Farsi, German, Hebrew, Hindi, Pashto, Spanish, Turkish, Urdu–and English. The model most in use is the Persian (Farsi), of which Hafiz (1325-1389)–that makes him a contemporary of Chaucer’s–is the acknowledged master, his tomb in Shiraz a place of pilgrimage; Ghalib (1797-1869) is the acknowledged master of that model in Urdu . . . [Garcia] Lorca also wrote ghazals–gacelas–taking his cues from the Arabic form and thus citing in his catholic (that is, universal) way the history of Muslim Andalusia.

And here is the technical definition of the Ghazal:

The ghazal is made up of couplets, each autonomous, thematically and emotionally complete in itself: One couplet may be comic, another tragic, another romantic, another religious, another political. (There is, underlying a ghazal, a profound and complex cultural unity, built on association and memory and expectation, as well as an implicit recognition of the human personality and its infinite variety.) A couplet may be quoted by itself without in any way violating a context–there is no context, as such. . . . The opening couplet (called matla sets up a scheme (of rhyme–called qafia; and refrain– called radif) by having it occur in both lines– the rhyme immediately preceding the refrain–and then this scheme occurs only in the second line of each succeeding couplet. That is, once a poet establishes the scheme–with total freedom, I might add–she or he becomes its slave. What results in the rest of the poem is the alluring tension of a slave trying to master the master. A ghazal has five couplets at least; there is no maximum limit.

Later in the introduction Ali explores his own struggle with the question of how the form may be adapted/translated to English. The collection itself has English ghazals by many established American poets (and some Indian ones) who were invited by Ali to try their hand at the form. By way of concluding, let me quote from my favorite in the collection, John Hollander’s “Ghazal on Ghazals”:

For couplets the ghazal is prime; at the end

Of each one’s a refrain like a chime: “at the end.”

But in subsequent couplets throughout the whole poem,

It’s this second line only will rhyme at the end.

On a string of such strange, unpronounceable fruits,

How fine the familiar old lime at the end!

All our writing is silent, the dance of the hand,

So that what it comes down to’s all mime, at the end.

[…]

There are so many sounds! A poem having one rhyme?

–A good life with a sad, minor crime at the end.

Each new couplet’s a different ascent: no great peak,

But a low hill quite easy to climb at the end.

Two armed bandits: start out with a great wad of green

Thoughts, but you’re left with a dime at the end.

Each assertion’s a knot which must shorten, alas,

This long-worded rope of which I’m at the end.

Now Qafia Radif has grown weary, like life,

At the game he’s been wasting his time at.

This piece is a revised version of the piece which first appeared in Lehigh.