His torment began the day he felt shortness of breath, excessive drowsiness and persistent nausea. Without reading much into those symptoms, Abdul Samad casually took a Paracetamol pill. But days later, when he was rushed to a city hospital, almost in a comatose state, he was left stunned, when diagnosed with kidney failure.

Once chronic renal (kidney) failure is diagnosed, the only options available with a patient are dialysis or a transplant. Dialysis remains a weekly process (or higher frequency), depending on the case. And if donor is available, a transplant is preferred. In both cases, the trauma suffered by the patient is huge; emotionally as well as financially.

After diagnosed with the critical disease, Samad’s family firmly stood by his side. His two sons volunteered for kidney donation. But his wife and mother of their children instead donated her own organ. A year later, the couple is doing absolutely fine.

Samad’s wife is a typical Kashmiri homemaker—who prefers family, over her own individualistic self.

Interestingly, the donor records maintained by Srinagar’s premier health institute, SKIMS show that 60 percent kidney donors are women—especially, wives remain at the forefront of the organ donation.

“In 20 percent cases where husbands learn about renal failure of their wives, they immediate seek divorce,” says a senior nephrologist posted in SKIMS. “Such men don’t even bother about the woman’s health as they believe their partner is replaceable with someone who’s not defective, and hence the decision comes easy.”

Much of that indifference comes from the larger societal belief that women have to carry the burden of being perfect. “And that’s what they’re conditioned as,” says Suraya Hassan, a doctorate scholar in gender studies. “The way they walk, sit, eat and sleep, everything is monitored. And they’re constantly told to put on their best behaviors. Hence when detected with a chronic disease, the perfect woman disappears and the men go in search of another perfect life partner.”

Also, Suraya says, women are told how everything in their life is their marriage, husband and kids. While the male usually gets choice without facing probing society, the label of being a woman divorcee or a widow is seen as a taboo.

“It’s difficult for a woman to get married, even if engagement was called off,” the scholar says. “Hence most of the ladies tend to save their partners instead of letting them die by donating their kidney.”

But donating organ—even to one’s father, son, spouse, or sibling—requires lot of guts and gumption. This is where Kashmiri women, already facing a host of issues due to the dogged conflict in the valley, make another soundless sacrifice.

On the whole, renal failure is a costly and life consuming disease, caused by diabetes, high blood pressure, nephrotic syndrome and polycystic kidney disease. Due to the nature of the illness, the stories of the donors are pretty astonishing.

In SKIMS’ Nephrology Department, an 18-year-old teenager had lately turned up for the post-surgical follow-up. Her name is Saima, who had donated her kidney to her father.

Despite having two brothers who had decided against kidney transplant, she went ahead to save her father’s life.

The doctors speak high of the youngster, and remember her touching words at the time of donation: “Mai apne baap ko aise marne nahi dungi” (I won’t let my father die like this.)

After the transplant, her brothers might be finding it hard to even make an eye-contact with their kid-sister, but that’s hardly on Saima’s mind.

“The most important task has been accomplished,” she beams over her father’s wellness after kidney transplantation. “Rest, it hardly matters. At the end of the day, one of us in family has to always walk an extra mile to comfort each other. I don’t think I’ve done something exemplary.”

Saima might be modest about her sacrifice, but some donors do feel jittery after renal failure jeopardizes their loved one’s life.

If a transplant is successful, the patient can survive from a year to 20 years, depending on his/her health condition. The only issue with an organ transplant, however, is the rejection of the organ by the body.

And to reduce such failed transplants, it’s preferred that the organ comes from a blood relation, which reduces the need for immune-suppressants and further diseases.

Kulgam sisters just did that, when their mother was diagnosed with kidney failure in recent past. The doctors recall their tenacity to compete with each other for organ donation as moving.

“But the only problem in their case was that both of them were still unmarried and it was most likely that donation would’ve hindered their search for a match later,” says a doctor who attending the case. “Or worse still, it might’ve even posed some serious health issue to them while conceiving.”

After counseled by doctors on those lines, one of the sisters reconsidered her decision, but the other stood adamant. A month later, the doctors went ahead with the transplant, resulting in both the daughter-mother being healthy at the moment.

“In that case as well,” the doctor rues, “no men came forward for the donation.”

Amid these bitter-sweet kidney transplant experiences, the renal failure disease is growing in the valley, with 30 new cases reported to SKIMS every month. If similar cases from SMHS are to be taken into account, it should add up to 50 new cases of renal failure per month.

Since the cost of treatment was high earlier, 90 percent cases couldn’t afford treatment. But with the opening of dialysis centers at every district hospital with nominal prices from the government and the initiatives taken by NGOs, 60 percent patients can afford to get treated.

But some hiccups and hitches, however, still make the entire process arduous for many patients. A young woman Shiraza’s case in this regard is very interesting.

After her father Mohammad Abdullah Najar suffered from the renal failure, she volunteered for the transplant. But since his father was associated with Jamaat-e-Islami, the doctors tried persuading him against the donation by his daughter citing religion as reference.

But as the donor went ahead, the patient later told the doctors that he would consider his daughter as a son onwards, especially when it comes to inheritance.

Such heartwarming cases do make SKIMS’ kidney transplant centre as a humanistic hub, than simply a body-mechanical workstation.

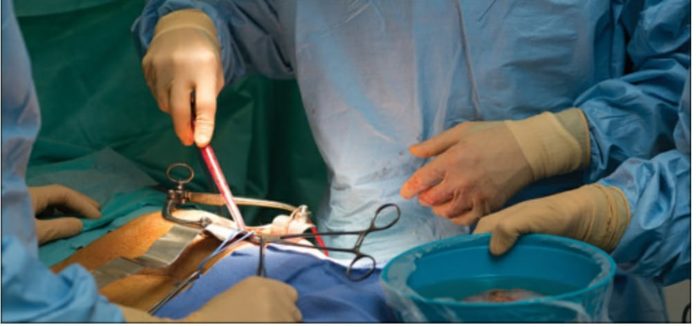

Four times in a month, kidney transplants are being performed here. As more surgeries cannot be accommodated in the hospital schedule, some 20 patients remain in waiting list, ready to be operated upon.

Since 2001, the institute has operated on 144 cases.

In most of these cases, the couple equation remains at test. While some husbands file divorce, and move on after the detection of the disease, others stand by their life partners.

In 30 percent cases, the nephrologists say, husbands tend to be extremely caring and supportive. “There was this case of a Shia couple,” a young doctor explains. “One month into marriage, the wife was diagnosed with renal failure and all through her hospital stay, her husband was the only person by her side. But sadly, some 45 days later, she passed away, leaving her husband in tears and wails.”

Barring some of these standout instances where husbands show the unbending loyalty, it’s a wife—‘who’s the kidney of her husband’s life’—by leading in the couple donations, with around 70 percent.

Among many husbands alive today with the help of their wives’ kidneys is mercurial Farooq Abdullah.

Lately on his 50th wedding anniversary with his British wife, many wondered, if National Conference chief—known for his tongue-in-cheek comments—conveyed it to his kidney donor: “You’re the kidney of my life!”